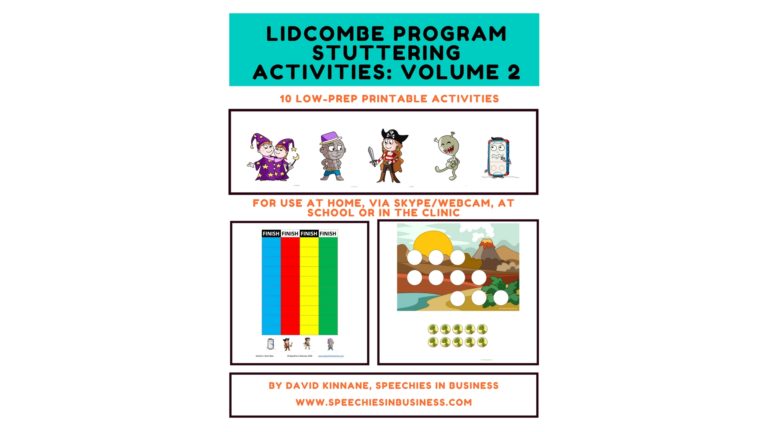

Lidcombe Program stuttering activities: Volume 2 printable activities for face-to-face and telehealth therapy now available

When we published The Lidcombe Program for stuttering: my 10 favourite therapy activities back in 2014, we had no idea how popular it would be. Thousands of people from more than 20 countries have downloaded our free resource. Feedback has been overwhelmingly positive, with many parents and speech pathologists reaching out to thank us for sharing…